INTEREST. The film shows a practical experiment to establish a new African settlement in tsetse-fly country.

The film opens with a ...

The Bantu Educational Kinema Experiment (BEKE) was a short-lived but hugely influential experiment in filmmaking for African audiences. Between March 1935 and May 1937, it produced 35 films and, through its travelling mobile cinema van, exhibited these pictures across Tanganyika, Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia, Kenya and Uganda. It represented, as film historian James Burns has argued, ‘the culmination of a decade of discussion and experimentation into the production of motion pictures for the subjects of the British Empire’ (Burns, 2002, 22). It would in turn shape colonial cinema campaigns – in terms of the representational requirements, its didactic function, and exhibition contexts for African audiences – for the remainder of the colonial era (Burns, 2002, 22).

Members of the Colonial Office had discussed the potential use of film within Africa at a Colonial conference in 1927 and reiterated these thoughts in a widely quoted 1932 report, The Film in National Life. In a section entitled ‘The Cinema and the Empire’, the Colonial Office outlined the potential value of film for African audiences as a pedagogical tool and as a means of social administration, while also noting the damage that could be caused by exhibiting inappropriate material. ‘The backward races within the Empire’, they wrote, ‘can gain more and suffer more from the film than the sophisticated European, because to them the power of the medium is intensified’ (The Film in National Life, 1932, 126).

This growing interest in African film audiences prompted the Colonial Advisory Committee on Native Education to send the noted biologist Julian Huxley to East Africa in 1929 to screen three films of varying complexities to children at government schools. One of these films was Black Cotton. His findings prompted the Colonial Office to invite Dr A. R. Paterson, a medical officer with the Kenyan government, to submit a plan for film production in East Africa (Burns, 2002, 25). Although Paterson’s plans were rejected for economic reasons, the Colonial Office did support a similar proposal from the American Congregational Missionary, John Merle Davis, after he secured $55,000 from the Carnegie Corporation and smaller grants from Northern Rhodesia’s Roan Antelope Mines and Mufulira Copper Mines (Reynolds, 2009, 61).

Davis’ proposed project was motivated by an interest in the social impact on local villages of mass labour migration to Northern Rhodesia’s Copperbelt (the subject of his influential 1932 report Modern Industry and the African). He sought to use film as a means of bridging and re-configuring the increasing divisions between the young, mission-educated elite and their unschooled tribal elders. As African film historian Glenn Reynolds argues, Davis’ proposal responded to ‘missionary concern over the perceived social disruptions to those African villages serving as labor reservoirs for Northern Rhodesia’s Copperbelt’. One of these perceived social disruptions was cinema itself, so that the BEKE, as it became known, was ‘partly designed to “capture” African viewers and correct the “falsehoods” perpetuated by the Hollywood dream machine’ (Reynolds, 2009, 71, 61). Indeed, James Burns argued that as the BEKE sought to produce enough films to completely restrict the exhibition of commercial productions, the project ‘was not merely an attempt to teach through films, but was also a form of proactive censorship’ (Burns, 2002, 27).

Davis’ original proposal included an investigation into censorship regulations and into the role of educational cinema within three territories: the Soviet Union, Egypt and Northern Rhodesia. At the request of the Carnegie Corporation, the project was revised to focus entirely on film production and exhibition within the five African territories (Reynolds, 2009, 60). In describing the aims of the project to the Seventh Imperial Social Hygiene Congress, Davis explained that it was ‘essentially a missionary undertaking’, intended to ‘enrich the entertainment and recreational life of the new Christian native community’. He outlined three aims. The first, he explained, was to uncover ‘the African’s preference for films’. The second to determine ‘the technique of film production best suited to the mentality of different types of Africans – the educated, the partially detribalised native, the primitive villager’. And the third to examine ‘the technique of displaying films to Africans – how far they wish to participate in the performance’ (Kinematograph Weekly, 18 July 1935, 23).

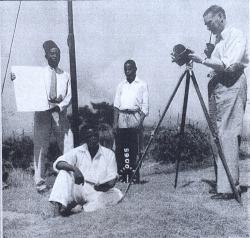

The BEKE was officially born on 1 March 1935, with an abandoned German sanatorium in Vugiri, Tanganyika serving as field headquarters. The two men charged with running the project were Leslie A. Notcutt, a supervisor on an East African sisal plantation with amateur filmmaking experience, who now served as Field Director, and Geoffrey Latham, a former director of Native Education in Northern Rhodesia, who was charged with overseeing the BEKE’s exhibition circuit and gauging audience reactions to the films in his role as Educational Director (Reynolds, 2009, 61).

In their detailed report on the BEKE (The African and the Cinema), published in 1937, Notcutt and Latham divided the project into three phases. The first saw the production of 13 films, which were widely exhibited, as the unit covered over 9,000 miles by road, in addition to short trips by rail and lake, between 4 September 1935 and 13 February 1936. During this period, the unit gave 95 performances, attended by approximately 80,000 Africans, 1,300 Europeans and a large number of Indians. ‘Usually’, they explained, ‘90 to 95% of the audience had never seen a moving picture before’ (Latham and Notcutt, 1937, 98).

This first batch of films covered a wide range of genres and subjects, beginning with Post Office Savings Bank, which adopted the Mr Wise and Mr Foolish format (this would be widely used in colonial cinema over the next thirty years, for example in Central African Film Unit productions like The Two Farmers). First Farce, the thirteenth and last film in this initial series, tested the African audience’s perceived preference for slapstick, while other titles were classified ‘instructional’ (for example Soil Erosion, and Hides) or presented morality tales within a fictional framework (Gumu). Further films addressed topical issues (such as Tax, which received a‘certain amount of criticism and was not often shown’) or responded more specifically to this generational conflict between the old and the new (The Chief). The filmmakers suggested that the topics shared a common theme, which they described as ‘progress vs African methods’ (Notcutt and Latham, 1937; Burns, 2002, 27).

Despite delays in securing further funding, Notcutt and Latham began filming a second batch of short subjects in August 1936 after receiving a loan from the Tanganyika government. These productions focussed predominantly on agricultural and health subjects, teaching new farming methods and promoting western medicine, and included African Peasant Farms, Tropical Hookworm, and The Veterinary Training of African Natives, the three surviving films housed at the BFI National Archive. Further financial shortages delayed production on a final group of films until January 1937. This third batch was ‘made to the order of the Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika Governments’ and was ‘entirely concerned’ with agriculture and animal husbandry (Notcutt and Latham, 1937, 63, 132).

The films were shot on 16mm and silent, but used the technique of sound-on-disc. Silent films with intertitles were avoided as most of the audience was illiterate, while talkies were problematic on account of the huge number of languages spoken. When touring with the first twelve films, Latham used disks in seven languages and on other occasions a local commentator was used – a tactic subsequently employed by the Colonial Film Unit. The films were nearly always shown outdoors on a 10’ x 8’ screen, with loudspeakers either side of it and the projector box positioned 63 feet away across the sides of the lorry (Notcutt and Latham, 1937, 171). The show was often preceded by some records and usually played to an audience of between 300 to 450 people. It often ended with an ‘interest’ film shot in England by BEKE cameraman Captain Coley, showing shots of London (titles included White People, parts one, two and three) and finally with a picture of the King and a performance of the National Anthem (Reynolds, 2009, 64).

These clear manifestations, and indeed celebrations, of colonial power appear somewhat at odds with the BEKE’s widely promoted African identity. Reports repeatedly explained that the BEKE was making films ‘in Africa for the Africans with Africans acting in them’, while Latham added that the African viewer’s ‘joy at seeing actors of their own race in the familiar setting of tribal surroundings is tremendous’ (Commercial Film, 1 April 1935, 2; Today’s Cinema, 18 December 1935). Rosaleen Smyth has argued that the BEKE organisers were ‘emphatic about the “Africanness” of their films’, soliciting advice from elite Africans during filming, offering a prize to African students at Makerere College for the best screenplay and training Africans ‘in all aspects of production and exhibition’ (Smyth, 1979, 443). Furthermore, film historian David Kerr recognised the creative influence of the local commentators, in creating a ‘context whereby the “gate-keepers” of the new media were not only the colonial film-makers but local urbanised Africans who could offer their own reinterpretation of the films’ (Kerr, 1993). The unit sought black input – and indeed asked Paul Robeson to sit on the advisory board (he declined) – although many historical accounts have suggested that the paternalism of the missionaries and the Colonial Office restricted any meaningful African involvement (Reynolds, 2009, 64, 66).

Formally, the films largely follow, and indeed endorse, a method of filmmaking which was gaining increasing orthodoxy during this period and which catered for the supposed different cognitive abilities of the African viewer. This method was championed by William Sellers, a Medical Officer with the Nigerian Government, who made a series of films for African audiences in the 1920s, including Anti-Plague Operations in Lagos. Sellers’ ‘rules’ for African audiences included an increased length in scenes (Latham also wrote that ‘more time must be given to most of the shots’), the removal of all extraneous movement or activity within the frame, the reduction of editing, fades and flashbacks and the removal of panning shots – ‘show him [the African] a vertical pan and he will tell you he saw the buildings sink into the ground’ (Sellers, Documentary News Letter, September 1941, 173, Latham, Sight and Sound, 123). However, these BEKE films did, on occasion, break from Sellers’ parameters, for example in their use of close-ups, but even here the films sought to educate the viewer in film language by deliberately displaying the artifice and process of the close-up.

On 27 May 1937, the final meeting of the BEKE’s Advisory Council convened at Edinburgh House to conclude the project. Davis, Latham and Notcutt had all pushed for its continuation, but this was reliant on funding from the colonial governments. While the Northern Rhodesian government ‘agreed unconditionally to co-operate’, the other four territories declined the invitation, with Kenya and Nyasaland deeming the films too amateurish. The films continued to tour over the next year, while Notcutt sought out additional venues (including the Mines’ Compound Cinema Circuit, which rejected his proposal as its shows were intended primarily as entertainment) (Reynolds, 2009, 70).

Despite its short lifespan, the BEKE greatly influenced the British government’s subsequent use of film within Africa. In their final report, Notcutt and Latham proposed a scheme ‘for putting the production of films for backward races on a permanent footing’. The Times wrote that this scheme ‘envisages the formation of a central organisation in London, supported by and serving all Colonies desiring to participate, with local film production units in each territory or group of territories’ and deemed this a scheme ‘emphatically worth careful study’ (The Times, 30 November 1937, 19). Within two years, the Colonial Office had established the London-run Colonial Film Unit, which sought to make films specifically tailored for African audiences (and using African personnel), exhibiting these pictures primarily though a network of mobile cinema vans. The majority of the CFU’s wartime productions depicted scenes in England, yet they were tailored specifically for African audiences and still closely followed the results and writings of Notcutt and Latham. Notcutt had stated in 1936 that it is ‘desirable that films of Europe and other parts of the world should be specially taken, or at any rate re-edited, for exhibition to the natives’. ‘The African should be given films which show the more simple home and rural side of western life’, he argued, ‘and which taken all together give a more true and balanced idea of the white man’s life and character’ (Notcutt, Sight and Sound, 124). His suggestions appear to have been met in the very first CFU film, Mr English at Home. Indeed the links between the BEKE and the CFU could have been stronger still, had Latham succeeded in his application for the position of director of the CFU. Instead he lost out to William Sellers, but he still declared his support for a scheme, which he hoped would serve as ‘an insurance against future exploitation of the cinema in Africa’ (Reynolds, 2009, 71).

Tom Rice (January 2010)

Works cited

Burns, J. M., Flickering Shadows: Cinema and Identity in Colonial Zimbabwe (Ohio: Ohio University Research in International Studies, 2002).

‘Nine Men and the Kinema: Great Use of a Great Invention’, The Children’s Newspaper, 31 August 1935, 8.

‘Fifty Million African ”Fans”: Big Scheme for Teaching Blacks by Film’, Commercial Film, 1 April 1935, 2, 19.

Commission on Educational Films, The Film in National Life (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1932).

Kerr, David, ‘The Best of Both Worlds? Colonial Film Policy and Practice in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland’, Critical Arts, Volume 7 (1993), 11-42.

‘Native Kinemas in East Africa’, Kinematograph Weekly, 18 July 1935, 23.

Latham, G.C., ‘Films for Africans’, Sight and Sound, Winter 1936/1937, 123-125.

Notcutt, L.A. and G.C. Latham, The African and the Cinema : An Account of the Work of the Bantu Educational Cinema Experiment during the Period March 1935 to May 1937 (London: Edinburgh House Press, 1937).

Reynolds, Glenn, ‘The Bantu Educational Kinema Experiment and the Struggle for Hegemony in British East and Central Africa, 1935-1937’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 29:1, March 2009, 57-78.

Sellers, William, ‘Films For Primitive People’, Documentary News Letter (September 1941), 173-174.

‘Bantu Educational Kinema Experiment’, Sight and Sound, Summer 1936, 38.

Ssali, Mike Hilary, ‘The Development and Role of an African Film Industry in East Africa, with Special Reference to Tanzania, 1922-1984’, PHD Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1988.

Smyth, Rosaleen, ‘The Development of British Colonial Film Policy, 1927-1939, with Special Reference to East and Central Africa’, The Journal of African History, Vol. 20, No. 3 (1979), 437-450.

‘African Films for Africans’, The Times, 30 November 1937, 19.

‘African Films for Africa’, Today’s Cinema, 18 December 1935, 25.

‘Films for African Natives’, Today’s Cinema, 27 May 1936, 31.

See also

‘International Missionary Council: The Bantu Educational Kinema Experiement (1936-1937), CO323/1356/4, accessed at National Archives.

‘Production and Circulation of Films for Natives of South, Central and East Africa: Bantu Educational Kinema Experiment’ (1938), CO323/1535/2, accessed at the National Archives.

‘British Film Institute: Sub-=Committee on Local Cinematography Scheme in Africa’ (1934), CO323/1252/16, accessed at National Archives.

‘International Missionary Council: Production and Circulation of Educational Films for Natives of South, Central and East Africa’ (1934), CO323/1253/5, accessed at National Archives.

‘International Missionary Council: Production and Circulation of Educational Films for Natives of South, Central and East Africa’ (1935), CO323/1316/5, accessed at National Archives.

‘International Missionary Council: Production and Circulation of Educational Films for Natives of South, Central and East Africa’ (1937), CO323/1421/10, accessed at National Archives.

‘International Missionary Council: Production and Circulation of Educational Films for Natives of South, Central and East Africa’ (1937/1938), CO323/1421/11, accessed at National Archives.